Today, Madagascar produces more than 70% of the world's vanilla, dominating global supply with beans from its northeastern SAVA region. But vanilla isn't native to Madagascar—it's a relatively recent arrival that transformed the island's economy and created a global dependency on a single origin. The story of how Madagascar became the vanilla capital of the world is one of colonial ambition, botanical innovation, and perfect terroir.

When Vanilla Arrived: The 1840s Introduction

Vanilla arrived in Madagascar in the early 1840s, brought by French colonists who recognized the island's potential for tropical agriculture. The exact date is debated, but most historical accounts place the introduction between 1840 and 1841.

The vanilla orchid (Vanilla planifolia) is native to Mexico and Central America, where it had been cultivated by the Totonac people and later the Aztecs for centuries. When the Spanish encountered vanilla in the 16th century, they brought it back to Europe, sparking attempts to cultivate it in tropical colonies around the world.

However, these early attempts failed spectacularly. Vanilla orchids would grow and flower in places like Réunion (then called Bourbon), Madagascar, and other tropical colonies, but they never produced beans. The reason was simple but not yet understood: vanilla's natural pollinator—the Melipona bee—existed only in Mexico.

The Breakthrough: Edmond Albius and Hand-Pollination

The key to Madagascar's vanilla future was discovered not in Madagascar, but on the neighboring island of Réunion in 1841. A 12-year-old enslaved boy named Edmond Albius developed a practical method for hand-pollinating vanilla flowers—a technique that remains essentially unchanged today.

Using a small stick or blade of grass, Albius demonstrated how to lift the rostellum (a flap separating the male and female parts of the vanilla flower) and press the pollen-bearing anther against the stigma. This simple gesture, performed within hours of the flower opening, allowed vanilla to fruit outside its native range for the first time.

News of this breakthrough spread quickly through the French colonial network. By the mid-1840s, French planters in Madagascar were applying Albius's technique, and the island's vanilla industry was born.

Where the First Crops Grew: The Northeast Coast

The first successful vanilla cultivation in Madagascar took root along the island's northeastern coast, particularly around the town of Antalaha and the broader region that would become known as SAVA (named for the towns of Sambava, Antalaha, Vohémar, and Andapa).

This region proved ideal for several reasons:

Climate perfection: The northeast coast receives abundant rainfall (80-120 inches annually), maintains year-round warmth (70-85°F), and enjoys high humidity—exactly what vanilla orchids require.

Volcanic soils: The region's red laterite soils, enriched by ancient volcanic activity, provide excellent drainage while retaining moisture and offering the slightly acidic pH vanilla prefers.

Natural shade: The coastal forests provided ready-made shade structures for vanilla vines, which require filtered sunlight rather than direct exposure.

Coastal proximity: Being near the coast facilitated export to Réunion and eventually to European markets, making commercial cultivation viable.

Early French planters established vanilla plantations in this region, often using enslaved or indentured labor to manage the intensive hand-pollination and curing processes.

Why Vanilla Spread So Quickly Across Madagascar

From these initial plantings in the 1840s, vanilla cultivation spread rapidly across Madagascar's eastern regions. By the 1880s, Madagascar was already competing with Mexico as a major vanilla supplier. By the early 20th century, it had surpassed all other origins. Several factors drove this remarkable expansion:

1. Ideal Growing Conditions Throughout the East Coast

The entire eastern coast of Madagascar—stretching hundreds of miles from north to south—shares similar climatic and soil conditions. Once vanilla proved successful in the SAVA region, it was logical to expand cultivation southward along the coast. Regions like Fénérive, Tamatave (Toamasina), and Maroantsetra all offered comparable conditions.

2. French Colonial Economic Policy

The French colonial administration actively promoted vanilla cultivation as a cash crop. They provided cuttings, technical assistance, and guaranteed markets for Malagasy vanilla. The colonial government saw vanilla as a way to make Madagascar economically productive and generate export revenue.

Infrastructure development—roads, ports, and administrative centers—followed vanilla cultivation, making it easier to expand production and get beans to market.

3. Low Barrier to Entry for Small Farmers

Unlike some plantation crops that require significant capital investment, vanilla could be cultivated on a small scale. A farmer with a few vanilla vines, some trees for support and shade, and the knowledge of hand-pollination could enter the vanilla market.

This accessibility meant that vanilla cultivation spread not just through large plantations but through thousands of small family farms. The knowledge of Albius's pollination technique spread person-to-person, village-to-village, creating a distributed network of vanilla producers.

4. Economic Incentive: High Value, Low Volume

Vanilla commanded high prices even in the 19th century. For farmers in rural Madagascar, vanilla offered a way to generate significant income from a relatively small plot of land. A few kilograms of cured vanilla beans could provide more income than much larger quantities of other crops.

This economic incentive drove rapid adoption. As word spread of vanilla's profitability, more farmers planted vines, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of expansion.

5. Curing Knowledge Transfer

Vanilla cultivation is only half the equation—proper curing is essential to develop the beans' flavor and market value. French planters and later Malagasy entrepreneurs developed and refined curing techniques suited to Madagascar's climate.

The traditional Bourbon curing method—involving blanching, sweating, sun-drying, and conditioning—was adapted to local conditions. As this knowledge spread, more regions could produce market-ready vanilla, not just green beans.

6. Market Demand and Mexican Decline

As European and American demand for vanilla grew in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Madagascar was positioned to meet it. Meanwhile, Mexico—vanilla's ancestral home—faced political instability, land reform challenges, and competition from synthetic vanillin (introduced in the 1870s).

Mexican vanilla production declined just as Madagascar's was expanding, creating a market vacuum that Malagasy vanilla filled. By the 1920s, Madagascar was the world's dominant supplier.

7. Quality Reputation

Madagascar vanilla—marketed as "Bourbon vanilla" (a reference to the former name of Réunion, not the whiskey)—developed a reputation for consistent quality and the classic vanilla flavor profile: creamy, sweet, with pronounced vanillin content.

This quality reputation created sustained demand, encouraging further expansion. Buyers knew that Madagascar vanilla would deliver the flavor they expected, creating market stability that supported continued investment in cultivation.

8. Generational Knowledge Building

As decades passed, vanilla cultivation became embedded in Malagasy culture, particularly in the SAVA region. Families passed down knowledge of pollination timing, vine management, harvest indicators, and curing techniques through generations.

This accumulated expertise made Madagascar increasingly efficient at vanilla production, reinforcing its competitive advantage over newer origins trying to enter the market.

The SAVA Region: The Heart of Global Vanilla

While vanilla spread across Madagascar's east coast, the SAVA region in the northeast remained—and remains—the epicenter of production. Today, SAVA produces approximately 80% of Madagascar's vanilla, which means this single region supplies roughly 60% of the world's vanilla.

The four towns that give SAVA its name each play a role:

- Sambava: The largest town and commercial hub, where much of the vanilla trade is centered

- Antalaha: Known as the "vanilla capital," with extensive vanilla warehouses and processing facilities

- Vohémar: Northern coastal town with significant vanilla cultivation in surrounding areas

- Andapa: Inland valley region with ideal microclimate for vanilla

The concentration of production in SAVA creates both opportunity and vulnerability. The region's expertise and infrastructure are unmatched, but natural disasters or political instability in this single area can disrupt global vanilla supply.

From 1840s Experiment to Global Dominance

The timeline of Madagascar's rise is remarkable:

- 1840-1841: Vanilla introduced to Madagascar from Réunion

- 1841: Edmond Albius develops hand-pollination technique on Réunion

- 1840s-1850s: First commercial vanilla plantings in northeastern Madagascar

- 1860s-1870s: Expansion along the east coast; Madagascar vanilla enters European markets

- 1880s-1890s: Madagascar becomes a major vanilla supplier, competing with Mexico

- 1900s-1920s: Madagascar surpasses Mexico as the world's largest producer

- 1930s-present: Madagascar maintains dominance, typically producing 60-80% of global vanilla

In less than a century, Madagascar went from having no vanilla at all to producing the majority of the world's supply—a transformation driven by botanical innovation, colonial economics, ideal terroir, and the labor of thousands of Malagasy farmers.

The Legacy and the Risk

Madagascar's dominance has created the modern vanilla market, but it's also created vulnerability. When cyclones strike SAVA, global vanilla prices spike. When political instability affects Madagascar, the entire vanilla supply chain feels the impact. When drought or disease affects Malagasy vines, there's no easy alternative source.

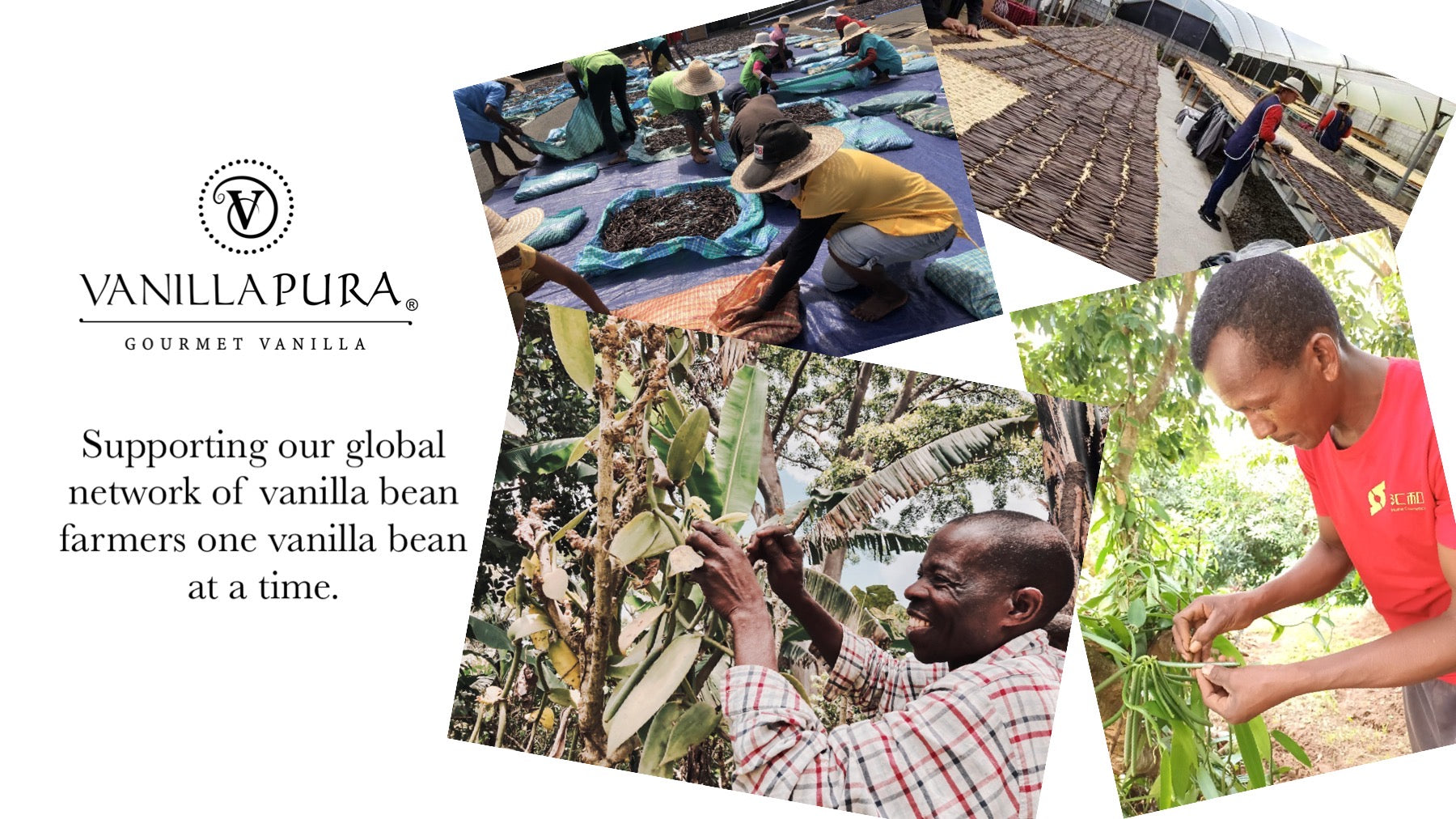

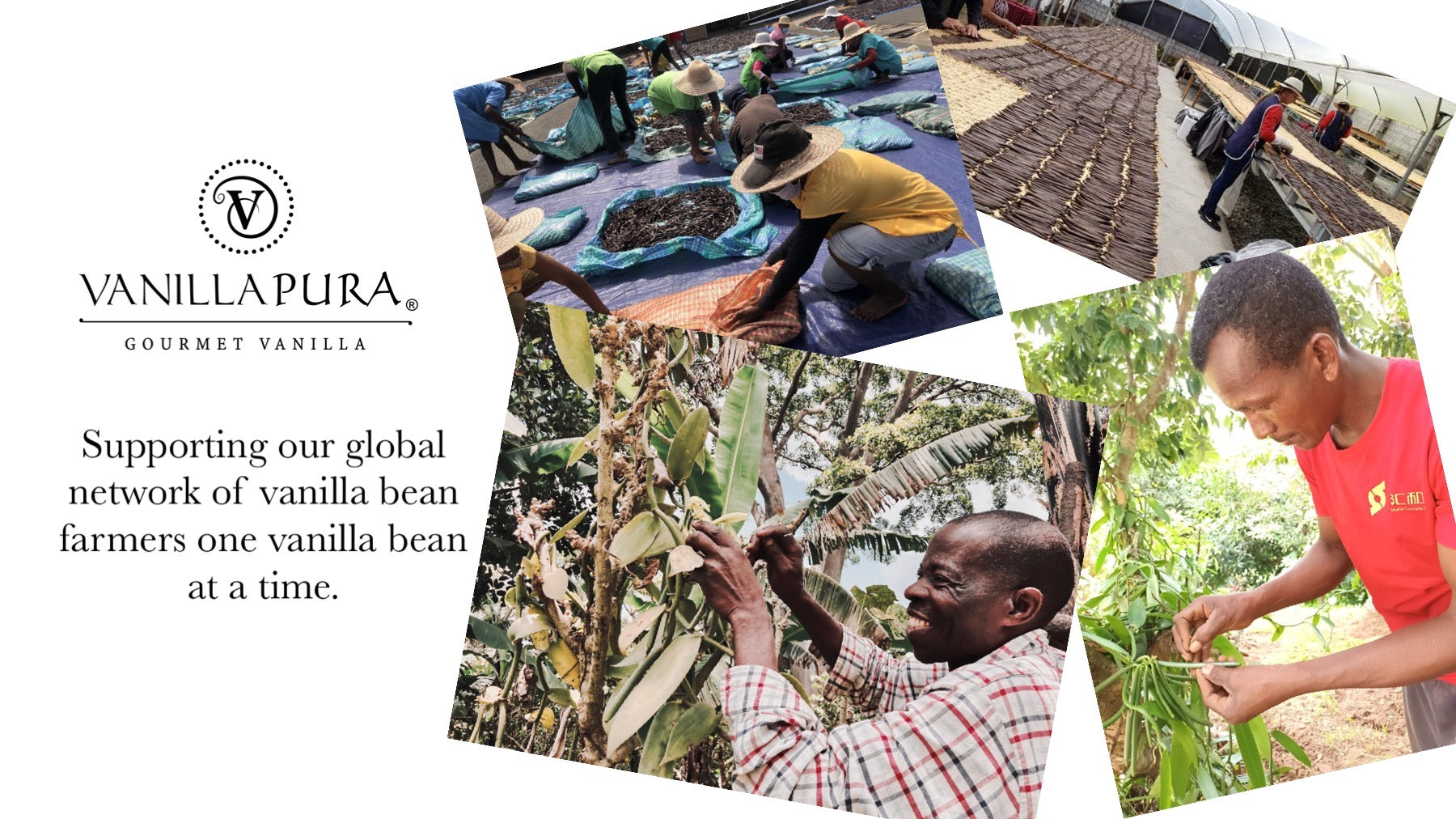

Efforts to diversify vanilla production—expanding cultivation in Uganda, Indonesia, India, and other origins—are partly motivated by the recognition that depending on a single island for 70% of a globally important spice is risky.

Yet Madagascar's advantages—170 years of accumulated expertise, ideal terroir, established infrastructure, and a quality reputation—are not easily replicated. The island that received its first vanilla cuttings in the 1840s remains, nearly two centuries later, the undisputed vanilla capital of the world.

A Remarkable Agricultural Story

The story of how Madagascar became the world's vanilla capital is one of the most remarkable in agricultural history. A plant native to Mexico, pollinated by a technique developed by an enslaved child on Réunion, found its perfect home on an island off the coast of Africa and transformed global flavor.

Every time you use Madagascar vanilla—whether in extract, whole beans, or paste—you're experiencing the result of this 170-year journey: from experimental plantings on the northeast coast to the SAVA region's vast vanilla forests, from Edmond Albius's simple gesture to the skilled hands of thousands of Malagasy farmers who continue his technique today.

Madagascar didn't just become the world's largest vanilla producer—it became synonymous with vanilla itself, a testament to the power of perfect terroir, human ingenuity, and generations of dedicated cultivation.