Not all places on Earth can grow vanilla. In fact, this precious crop can only thrive in a narrow band around the equator known as the "bean belt"—a region roughly between 10 and 20 degrees latitude north and south of the equator. Understanding why vanilla is confined to this zone reveals the delicate balance required to produce the world's most beloved flavor.

The Perfect Climate Zone

Vanilla orchids require very specific conditions to flourish: consistent warm temperatures between 70-85°F, high humidity, partial shade, and a distinct wet and dry season. But perhaps most critically, they need time—lots of it. From planting to first harvest takes three to four years, and the vines continue producing for many years after. This long cultivation cycle makes vanilla farming a patient investment that cannot afford catastrophic weather events.

The Equator's Protective Shield

Here's a fascinating fact that vanilla farmers depend on: hurricanes and typhoons never cross the equator. This meteorological phenomenon occurs because these massive storm systems require the Coriolis effect to form and maintain their rotation, and this effect is virtually zero at the equator itself. Regions closest to the equator enjoy a natural protection from these devastating storms, making them ideal for crops like vanilla that require years of undisturbed growth.

However, as you move further from the equator—even within the bean belt—the risk of tropical cyclones increases dramatically. This is where geography becomes destiny for vanilla farmers.

The Madagascar Catastrophe: A Cautionary Tale

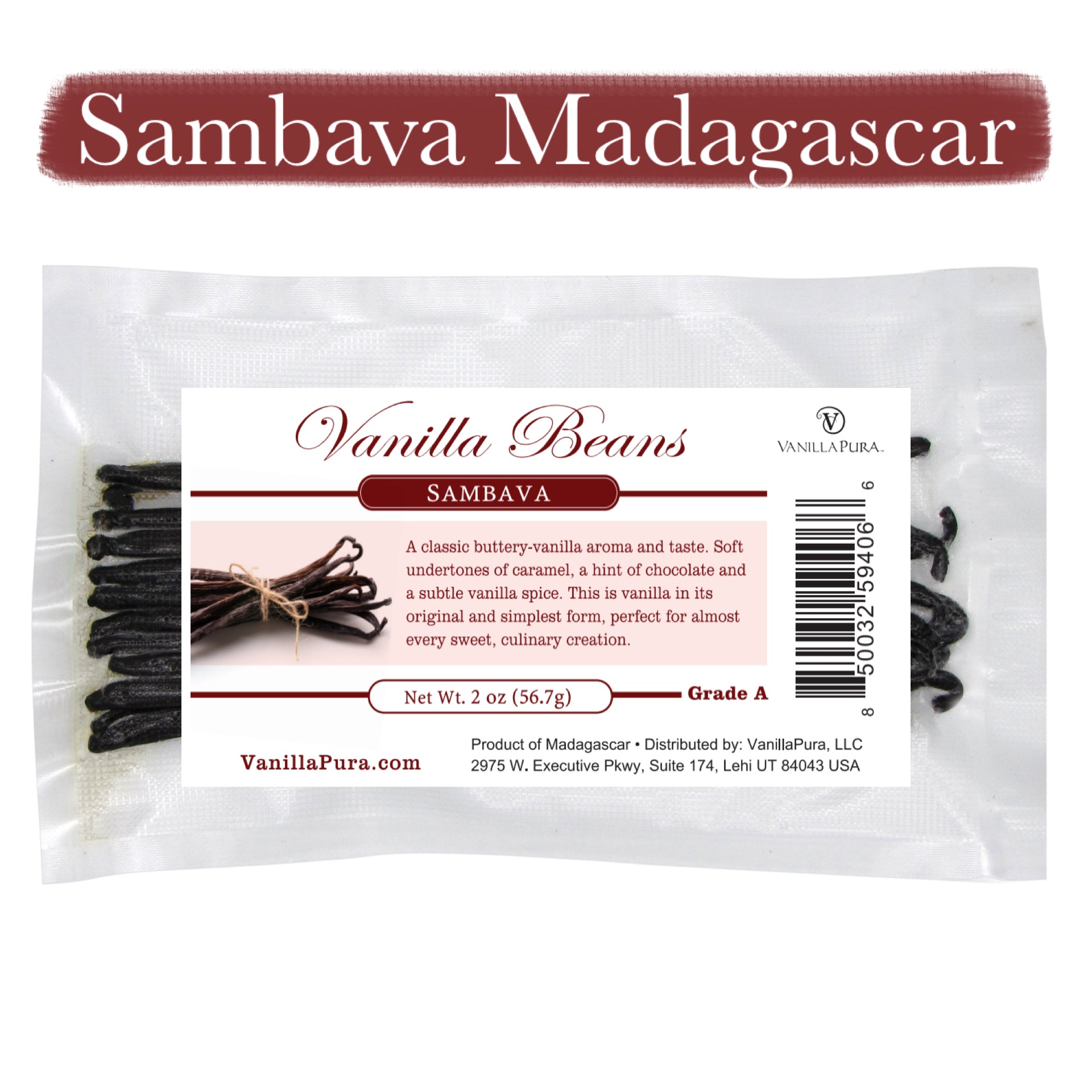

In March 2017, the world witnessed what happens when vanilla cultivation meets extreme weather. Cyclone Enawo, one of the strongest storms to hit Madagascar in over a decade, made landfall on the northeastern coast—the heart of the country's vanilla-growing region. Madagascar produces approximately 80% of the world's vanilla, and Enawo devastated the crop.

The destruction was catastrophic. Vanilla vines that had taken years to mature were ripped from their support trees. Curing houses were destroyed. Entire harvests were lost. The impact rippled across the global vanilla market almost immediately—prices skyrocketed to unprecedented levels, reaching over $600 per kilogram at their peak. Vanilla became more expensive per ounce than silver.

The Long Road to Recovery

The aftermath of Cyclone Enawo demonstrated just how vulnerable vanilla cultivation can be. It took Madagascar over five years to recover production levels, and during that time, the entire food and beverage industry felt the impact. Manufacturers reformulated products, sought alternatives, and consumers saw vanilla prices surge in everything from ice cream to baked goods.

This wasn't just about replanting vines—it was about waiting for those vines to mature, training them properly, and rebuilding the infrastructure and expertise that had been lost. The vanilla industry learned a hard lesson about the risks of concentration in regions further from the equator's protective zone.

Why the Bean Belt Matters More Than Ever

The Enawo disaster highlighted the importance of geographic diversity within the bean belt. While Madagascar remains the dominant producer, regions closer to the equator—such as Uganda, parts of Indonesia, and equatorial regions of Papua New Guinea—offer greater climate stability. These areas may not face the same hurricane risks, though they have their own challenges.

At VanillaPura, we understand that sourcing vanilla means understanding geography, climate patterns, and the years of patient cultivation required to bring these beans to your kitchen. The bean belt isn't just a growing region—it's a delicate ribbon of climate stability that makes vanilla possible. Every bean represents years of careful cultivation, the hope that weather will cooperate, and the dedication of farmers who work within nature's narrow parameters.

When you use premium vanilla, you're not just adding flavor—you're experiencing the result of perfect geography, patient cultivation, and the resilience of farmers who work within one of the world's most specific agricultural zones.